Centuries before the reformation began with Martin Luther, another reformation began. One that the Catholic Church struggles with even today.

The Waldensians, also known as Waldenses, Vallenses, Valdesi, or Vaudois, were a 12th-century Christian movement in Western Europe. originating with Peter Waldo (Valdes) of Lyons, France. Waldo was a wealthy merchant who gave it all up to live a life of poverty and preach the Gospel to the poor. To this end, he even funded a translation of the New Testament into French so that people could read the Scriptures in their own language, which was pretty extreme for that time. Originally known as the Poor of Lyon, the movement spread to the Cottian Alps in what is today France and Italy.

Origins

Although they rose to prominence in the twelfth century, there is some evidence to suggest that the Waldenses may have existed before Peter Waldo appeared on the scene, perhaps as early as 1100. The words of Pope Alexander 111 in 1179, at the Third Council of the Lateran when he complained lamented that the Waldenses were a “pest of long existence” support this. The Inquisitor, Reinerius Saccho in the thirteenth century also spoke about the dangers of the Waldenses for among other reasons its antiquity “some say that it has lasted from the time of Sylvester, others, from the time of the Apostles.” And in the seventeenth century, Waldensian Pastor Henri Arnaud stated that “the Vaudois are, in fact, descended from those refugees from Italy, who, after St Paul had preached the gospel there, abandoned their beautiful country, like the woman mentioned in the apocalypse and fled to those wild mountains where they have to this day, handed down the gospel from father to son in the same purity and simplicity as it was preached by St Paul.”

The Waldensians did not reject the Catholic Church and its teachings in its entirety but rather saw themselves as a “church within the Church”. This pre-Reformation group advocated for a return to biblical teachings, emphasizing the supreme authority of the Bible, voluntary poverty as a way to perfection, and personal piety. They rejected certain Roman Catholic Church practices such as purgatory, indulgences, and the veneration of saints, which were not found in the Bible. These viewpoints led to conflict with the established Catholic Church and the Waldensians’ condemnation as heretics, which resulted in severe persecution, but they survived, and their emphasis on the Bible and individual faith significantly influenced the Protestant Reformation.

Waldo and his followers developed a system whereby they would go from town to town and meet secretly with small groups of Waldensians. The traveling Waldensian preachers were known as ‘barbas’. They would be sheltered by the group, who would then help make arrangements for the ‘barba’ to move on to the next town in secret. Waldo probably died in the early thirteenth century, possibly in Germany. He was never captured, and his fate remains uncertain. Despite the Waldensians seeking recognition, the Catholic Church forbade them to preach without permission. They refused to obey, and the Council of Verona in 1184 excommunicated them. The Waldensians, in turn, excommunicated Pope Benedict XI.

Persecution

In 1211, more than 80 Waldensians were burned as heretics at Strasbourg. This was the beginning of several centuries of persecution that nearly destroyed the movement. In 1487 Pope Innocent VIII issued a bull Id Nostri Cordis for the extermination of the Vaudois. Alberto de’ Capitanei, archdeacon of Cremona, responded to the bull by organizing a crusade to fulfill its order, launching a military offensive in the provinces of Dauphiné and Piedmont. Charles I, Duke of Savoy, eventually interfered to save his territories from further turmoil and promised the Vaudois peace, but not before the offensive had devastated the area and many of the Vaudois had fled to Provence or south to Italy. When the Reform Movement spread throughout Europe, the Waldensians came to hear of it and decided they wanted to know more about this new Church movement.

They sent envoys to Berne, Basel and Strasbourg to hold discussions with Oecolampadius, Martin Bucer and William Farel, who was later present at the 1532 Waldensian synod in Chanforan (in the Waldensian Valleys of Italy). After several days of discussions, the Waldensians decided to join the Reform Movement and, in particular, to become followers of Zwingli and Bucer. They came out into the open and from then on refused to follow any Roman Catholic practices, built new “temples” and held services in public. Their pastors were attached to a particular parish and were no longer traveling preachers or “barbas”, as in the Middle Ages. But the attacks on their movement did not end there. They were subjected to severe and brutal persecutions, including torture and being burned at the stake. Massacres such as that at Merindol in 1545 and “Piedmont Easter” in 1655, where an estimated 1,700 Waldensians were slaughtered. This massacre was so brutal that it aroused indignation throughout Europe. It prompted John Milton’s poem on the Waldenses, “On the Late Massacre in Piedmont”.

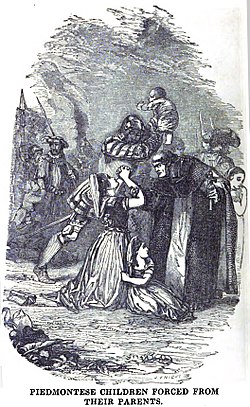

Swiss and Dutch Calvinists set up an “underground railroad” to bring many of the survivors north to Switzerland and even as far as the Dutch Republic, where the councillors of the city of Amsterdam chartered three ships to take some 167 Waldensians to their City Colony in the New World (Delaware) on Christmas Day 1656. Those who stayed behind in France and the Piedmont formed a guerrilla resistance movement led by a farmer, Joshua Janavel, which lasted into the 1660s. In 1685, Louis XIV revoked the 1598 Edict of Nantes, which had guaranteed freedom of religion to his Protestant subjects in France. French troops, sent into the French Waldensian areas of the Chisone and Susa Valleys in the Dauphiné, forced 8,000 Vaudois to convert to Catholicism and another 3,000 to leave for Germany. The Duke of Savoy, Victor Amadeus II, a nephew of Louis XIV, continued the anti-Waldensian policy of his uncle. In the decree of January 1686, he banished their pastors, forbade public worship, and forced parents to give their children a Roman Catholic baptism. The pastor Henri Arnaud advocated rebellion. The Waldensians were defeated in a short three-day war, and many died and 8500 were imprisoned. However, thanks to Swiss intervention, some managed to flee to Geneva.

In 1688, the political situation in Europe was turned upside down when William of Orange came to the English throne and formed a coalition against Louis XIV. He sent emissaries to the exiled Waldensians in Switzerland and secretly organised their return to the Piedmont Valleys in 1689. This episode is known as the “Glorious Return“. Only 900 men managed to get back to the Piedmont after enduring a march in terrible conditions, using a very unusual route. However, they arrived in Prali, in the Val Germanica, and were able to hold their first public service on 8th September 1689, led by pastor Henri Arnaud. They swore the oath of Sibaud on 11th September 1689, loyally promising to keep together and continue their fight for the Waldensian cause, with Arnaud as their military and religious leader. Victor Amadeus eventually broke off his alliance with France and became an ally of England. The Waldensians were saved. The English put pressure on the Duke of Savoy and made him issue a decree giving the Waldensians civil rights in their territories. Years of persecution continued, however, before they received full civil rights in 1848.

The movement persisted and, over time, adopted Calvinist theology, becoming the Waldensian Evangelical Church, an ancient Protestant church with a surviving presence in Italy and around the world to this day. Today, the Waldenses are governed by a seven-member board, called the Tavola (“Table”), elected annually by a general synod that convenes in Torre Pellice, Italy. In 2015, after a historic visit to a Waldensian Temple in Turin, Pope Francis, in the name of the Catholic Church, asked Waldensian Christians for forgiveness for their persecution. The Pope apologized for the Church’s “un-Christian and even inhumane positions and actions”. Read more about the Waldensians here:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Waldensians

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Waldenses

- for the Roman Catholic side of the Waldensian story https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/15527b.htm

- https://christianhistoryinstitute.org/magazine/article/an-ancient-and-undying-light